Enthusiasm is the answer

I recently had the pleasure of seeing Darren Criss (I had to stop myself from writing ‘The Great Darren…’) perform in Maybe Happy Ending. I’m not sure I have ever seen a musical theater performance better than his (nor a production as visionary or creative as Mr. Arden’s… please, see it.) What characterized Mr. Criss’s work, besides his remarkable talent and, no doubt, extraordinary preparation… was his pure, childlike enthusiasm. It’s the same thing that distinguishes him (if only a very little) from John Gallgher Jr., whose performance in Swept Away was also very special. Mr. Gallagher is, likewise, spectacularly talented and bursting with enthusiasm. But Darren was like a toddler up there; his inner child was pulling all the strings for him.

I look around my studio and the culture, generally, and see that enthusiasm has never been harder to come by. Amid all the talent – and there has never been more talent – enthusiasm has become most rare and precious. Artists are the bedrock of our cultural sea, and that is a privilege and a burden. We – musicians, architects, painters, actors, filmmakers – are the ones who make era-defining things. But being at the bottom also means that all the detritus that drifts down through the cultural consciousness eventually comes to rest upon our shoulders, and lately, the sediment has been heavy.

A few thoughts:

1. In The Arts, being “The Best” Begins and Ends with Enthusiasm: I was always brought up to work harder and harder to become “The Best,” as in the most skillful at all costs. I was raised by an athlete, and being friendly doesn’t matter in athletics. My dad coached me to be stronger and win the race. The athlete’s approach – the only one he knew – is fundamentally adversarial. Elite athletes are enthusiastic, yes, about burying their competition. But the enthusiasm of the artist, the kind I ended up needing, is not that of supremacy but of equality. The artist’s enthusiasm is about connecting with everyone around us. It’s about kinship and friendship and collaboration and creation. If the artist is brought up to be “The Best” in the athletic sense, they are launched on a disappointing, lonely voyage in the wrong direction.

People in the arts want to work with their friends, period. And unlike in sports, where players live and die by their numbers, this is always possible. In sports, being a great person only makes it more painful for the manager to tell you to clean out your locker. But being a great person in the arts often means you don’t have to.

2. Feedback Without Humility Will Destroy Your Enthusiasm:

You’ve just opened an email with some feedback from your manager or whoever:

CONFUSED

APPALLED

ANGRY

DISCOURAGED

EXHAUSTED

DEFEATED

Familiar?

What happens to those of us who operate under the delusion that we are the best when we receive feedback calling for improvement? We are appalled. We disagree. We hate the feedback. We question the sanity of the one who dared offer it. We are “confused,” and we are convinced that the feedback confuses us. “What does that even mean!?” was high in the running for my epitaph. But we’re not really confused, we’re just offended. We comprehend what “say it faster” or “do it a little less angry” means. But it offends us that after all of our hard work to get it perfect, some Danny Dumpster on a Zoom call has the stones to think they can make our “perfect” stuff better with some ham-handed note. But you know what… dammit, they’re probably right. They’re clumsy, but they’re probably right. Because DAMMIT, we’re not “The Best.” We’ve not got it perfect. I wish when I was young, I had the humility to take feedback… I would have improved a lot more, and I know I would have been a lot happier. My journals from that period are full of, “This idiot told me…” etc. After all, I was “The Best.”

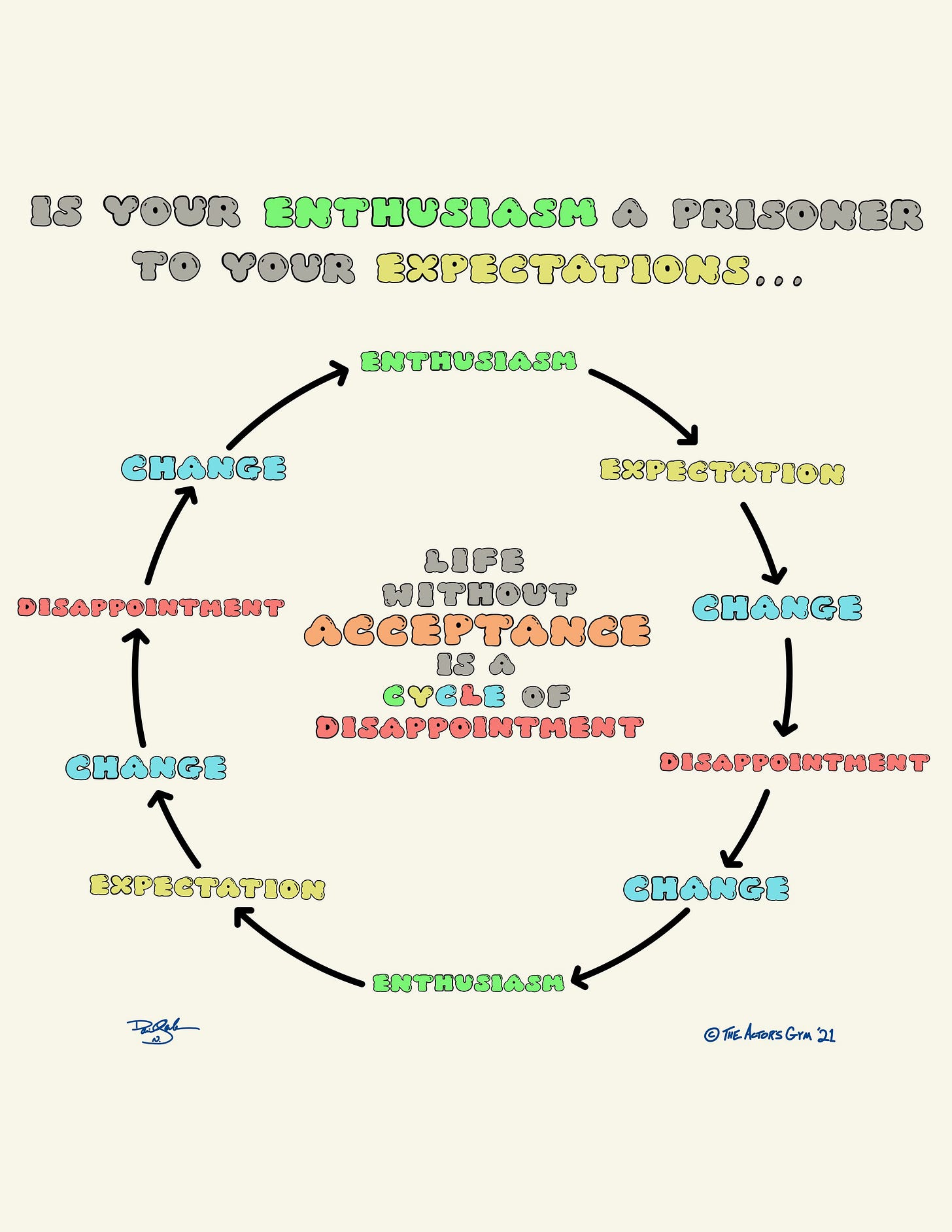

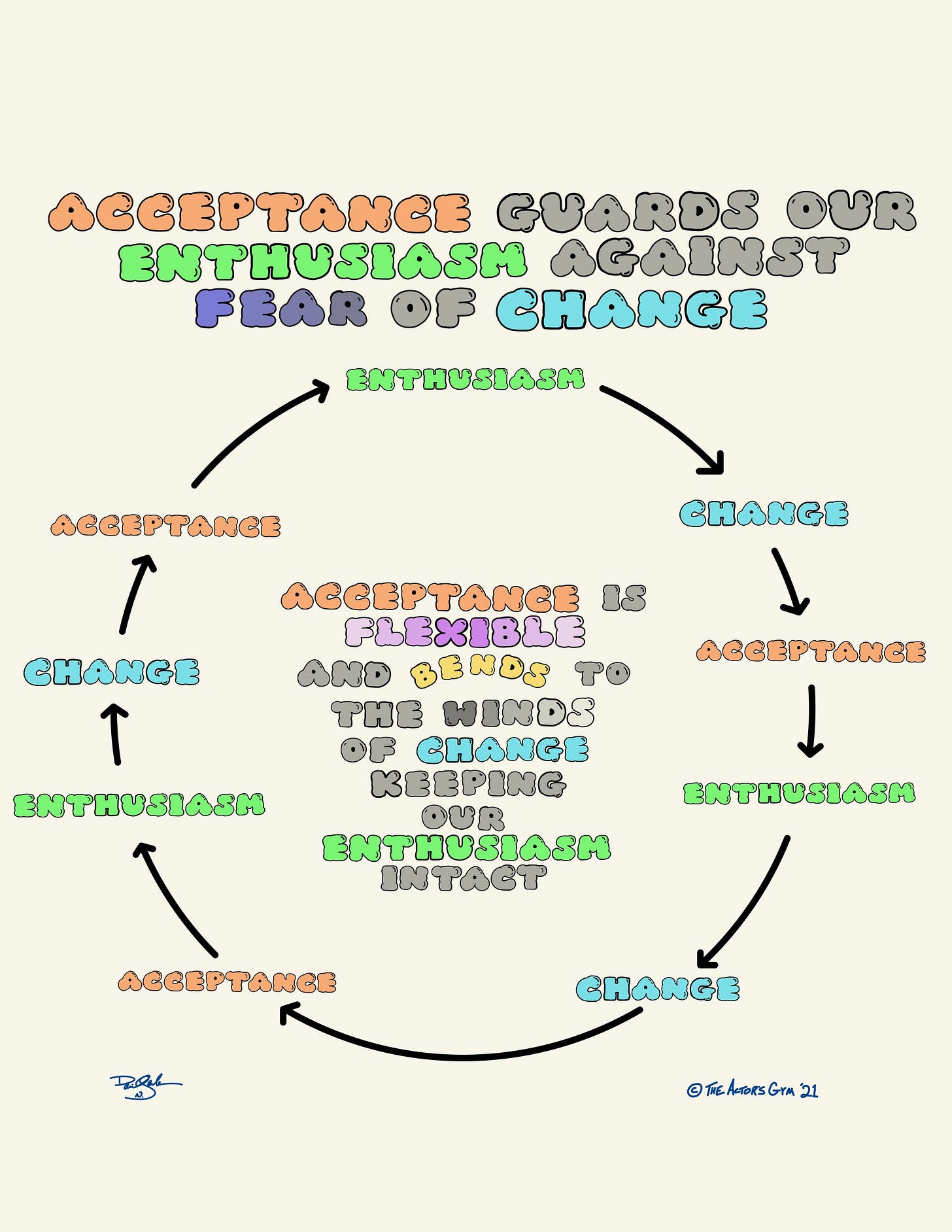

3. Resiliency: Enthusiasm cannot exist without resiliency, and our resiliency is bottoming out. If self-confidence is absolute, it will be too rigid, and instead of bending under pressure, it will snap. We’ve got to make our confidence malleable by infusing it with humility so we can absorb blunt feedback. Where we are bendy, we are resilient.

My confidence used to be stiff as a board, strong when unchallenged but like to shatter when tapped. Ultimately, this resulted in a major crisis of confidence and a more-or-less breakdown that I’d like to help you avoid: Our objective has got to be enthusiasm, not supremacy.

My plentiful enthusiasm slowly eroded under the flood waters of my delicate ego. I became certain the world was out to get me, that it didn’t see my value, that it was unfriendly. I hated the parts of myself I thought others viewed as imperfect, and that was a lot of parts. I was stubborn and afraid. My confidence was unyielding. I had no humility. I was not resilient. I didn’t want to be friends with anyone, which I internalized as “no one wants to be friends with me,” but the truth was that I was too afraid to be seen and disliked.

When we take this kind of fear into the world with us, it’s all we see. And we despise ourselves for the things we think have made other people lose interest: our body, our personality, our voice, our acting, whatever it may be (which it seldom is).

It’s taken me until I’m almost forty to realize that the world wants to be my friend, to put down my sword and see that it was me who was against me for all those years.

I’m not the most talented, and neither are you; no one is. What’s unique and magical about the arts is that to have interesting and fulfilling careers, we don’t have to be. Not even close. All we need is to be bizarrely and contagiously enthusiastic about what we do.

Really helpful, sobering, good stuff. I am the WORST with criticism, tryna get better.

This is really inspiring and encouraging. I feel invigorated.